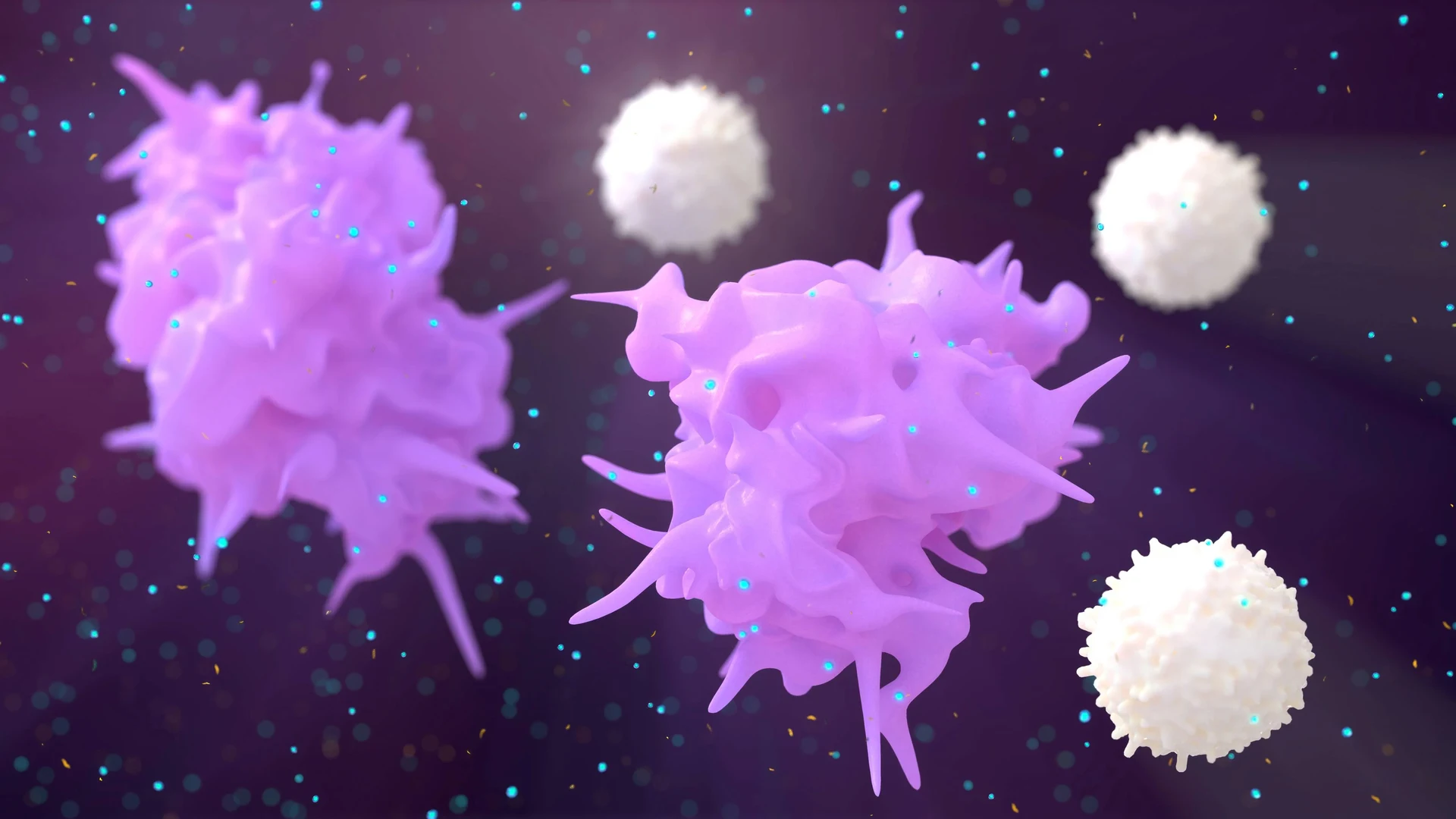

In allergic asthma, so-called ILC2 and Th2 cells are key drivers of inflammation. They produce messenger substances that increase mucus formation and the influx of immune cells. At the same time, the inflamed lung tissue is rich in free fatty acids and oxidative molecules—conditions that normally endanger cells.

The study shows that pathogenic ILC2s absorb large amounts of these fats and incorporate them into their membranes. In order to avoid dying from ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of cell death caused by oxidized lipids, they activate their antioxidant systems. The enzymes GPX4 and TXNRD1 play a central role in this process. They neutralize harmful lipid peroxides and enable the cells to survive and multiply despite the stressful environment.

“These immune cells operate in an environment that is actually toxic to them. They only survive because they ramp up their own protective programs to an extreme degree,” explains first author Chantal Wientjens, who conducts research in the Wilhelm working group at the Institute of Chemistry and Clinical Pharmacology at the UKB and is a doctoral student at the University of Bonn. “Our data show that as soon as we specifically disrupt this protection, the cells lose their ability to drive allergic inflammation.”

To test this approach, the Bonn team inhibited the thioredoxin metabolic pathway using a drug that blocks the enzyme TXNRD1. In mouse models, this led to significantly less ILC2 accumulating in the lungs. As a result, both the production of the typical type 2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 and the number of eosinophils and mucus production decreased. Overall, the allergic reaction was significantly less severe.

Study leader Christoph Wilhelm, Chair of Immunopathology at the Institute for Clinical Chemistry and Clinical harmacology at the UKB and member of the ImmunoSensation² Cluster of Excellence at the University of Bonn, explains: "Pathogenic type 2 immune cells are surprisingly dependent on their antioxidant ‘lifeline’. This opens up a new therapeutic venue: In the future, we could slow down the metabolism of overactive immune cells without weakening the immune system as a whole. This is an exciting prospect, even though we are still in the early stages of research."

The study underscores how closely immune function and metabolism are intertwined. In order to remain active in the high-fat and oxidative environment of the inflamed lung, pathogenic ILC2s flexibly adapt their metabolism—and in doing so, unintentionally create the very dependency that makes them vulnerable.