Content

A flood of data of Universe-sized proportions: big data in outer space

“It was overwhelming, a genuine explosion of joy,” says Professor Cristiano Porciani, thinking back to the moment when everyone realized that the Our Dynamic Universe cluster initiative was to become a full-fledged Cluster of Excellence. “Now we finally have the chance to deliver on what we’ve promised,” says a happy Porciani, who is Speaker for the new cluster at the University of Bonn. And the cluster—a joint initiative between the University of Bonn and the University of Cologne (the lead university)—is something truly special.

Essentially, Cristiano Porciani explains, the researchers will be trying to fill the gaps in our knowledge about how the Universe came to be. The structure and development of our Universe is shaped by countless phenomena that follow some very different timescales, ranging from fractions of a second to billions of years. “Astrophysicists have made major progress in recent decades in decoding the processes that go on in the Universe,” Cristiano Porciani says. “But there are still many unanswered questions.” This concerns both the Universe’s long-term future and extremely short-lived events such as when supernovae explode.

And existing technology is not good enough to close these gaps in our knowledge. As Porciani explains: “They’re currently building the Square Kilometre Array Observatory in Australia and South Africa.” The SKA, as it is known for short, will combine the signals from thousands of small antennas built across an area spanning several thousand kilometers. “In principle, the SKA will work like a huge radio telescope with an extremely high level of sensitivity and angular resolution.” This will allow it to conduct faster and more extensive all-sky surveys than existing telescopes. However, there is a challenge: “The SKA will generate data at a rate similar to the whole world’s daily Internet traffic.” Storing these amounts of data and analyzing them using existing technologies would simply not be affordable on technical grounds.

A bold approach

Analyzing these mountains of data will require new methods, and developing them is one of the aims of the new cluster. “Something we’ll be focusing on is coming up with artificial intelligence that can run efficient analyses on the vast quantities of data,” Porciani reveals. The cluster’s researchers, who straddle the boundaries between astrophysics, mathematics and computer science, plan to use new AI programs to evaluate the Universe’s “big data” on the fly. Instead of storing and analyzing each individual piece of data, the AI will take the tangled mass of information and only pick out those bits that are relevant and make them available for research. All the accompanying “noise” will be deleted there and then. “It’s a bold approach,” Porciani admits. “Because, as soon as we’ve processed the data, it’s gone. There’s no way of checking it after that.” To develop reliable tools of this kind, the members of the cluster are drawing inspiration from astroinformatics, a new field that uses advanced statistical methods taken from computer science, primarily machine learning and AI.

The cluster can rely on a wealth of expertise right on its doorstep for its project: besides the Universities of Cologne and Bonn, the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Forschungszentrum Jülich and the German Aerospace Center (DLR) are also on hand in the Bonn/Cologne region to contribute expertise and infrastructure. This ranges from building state-of-the-art detectors and instruments for international telescopes and leading large-scale observation programs through to running a world-class astrophysics laboratory and simulating the dynamic evolution of planets, stars and galaxies on high-performance computers. “Working together, we’re establishing a world-renowned center of expertise in our region, especially for radio astronomy,” Porciani says. “We want to use the new cluster to reinforce this leading position even further.” Completing the cluster is the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies.

“It’s my dream to understand how the inhomogeneities that emerged in the primordial Universe created the structures that we can observe today,” Porciani explains. “It’d also be fantastic to come up with computer simulations that map the dynamics of the Universe on all the scales, from the tiniest cosmic structures through to the big picture.”

And the new cluster could turn this dream into a reality.

If you think of “color” and “flavor,” you would undoubtedly not be alone in imagining some brightly colored candies. Physicists, however, think differently, because they know that color and flavor represent two fundamental forces of nature, referred to as the strong (“color”) and weak (“flavor”) interactions. The Color meets Flavor Cluster of Excellence is focusing on these forces in order to answer the really big questions: “Why is there only matter in the Universe?” “How does the strong interaction generate matter?” “And what is the secret of dark matter, which is believed to constitute the bulk of what makes up the Universe?” “We have a brilliant team that brings world-leading expertise at both experimental and theoretical level, so combining the two will bring us a long way toward answering these questions,” says a confident Professor Jochen Dingfelder, Speaker for the new cluster.

Together with their partners, the particle physicists at the University of Bonn intend to study the relationship between the strong and weak interactions in order to discover new physical phenomena. The researchers will be focusing specifically on quarks, the fundamental building blocks of matter. It is the strong interaction that holds them together and forms them into hadrons such as protons and neutrons, i.e. the component parts of nuclei. Meanwhile, the weak interaction is what enables particles to change their type (“flavor”), e.g. when a neutron decays into a proton, an electron and an antineutrino. Processes like this furnish important insights into the properties of particles—including potentially new ones that have so far eluded discovery. The Cluster of Excellence will also be studying the properties of the Higgs boson and searching for the axion, a hypothetical particle that plays a key role in the strong interaction and could also be a candidate for dark matter.

“Gaining a precise understanding of these processes requires more than simply observing the weak interaction—we also need to know all there is to know about its strong counterpart,” Dingfelder explains. “Only by understanding the interplay between the two forces will we achieve the high degree of precision that’s required to make fundamental headway in our understanding of nature and discover something new.”

My dream result would be to discover a new phenomenon in particle physics.

From low to extremely high energy

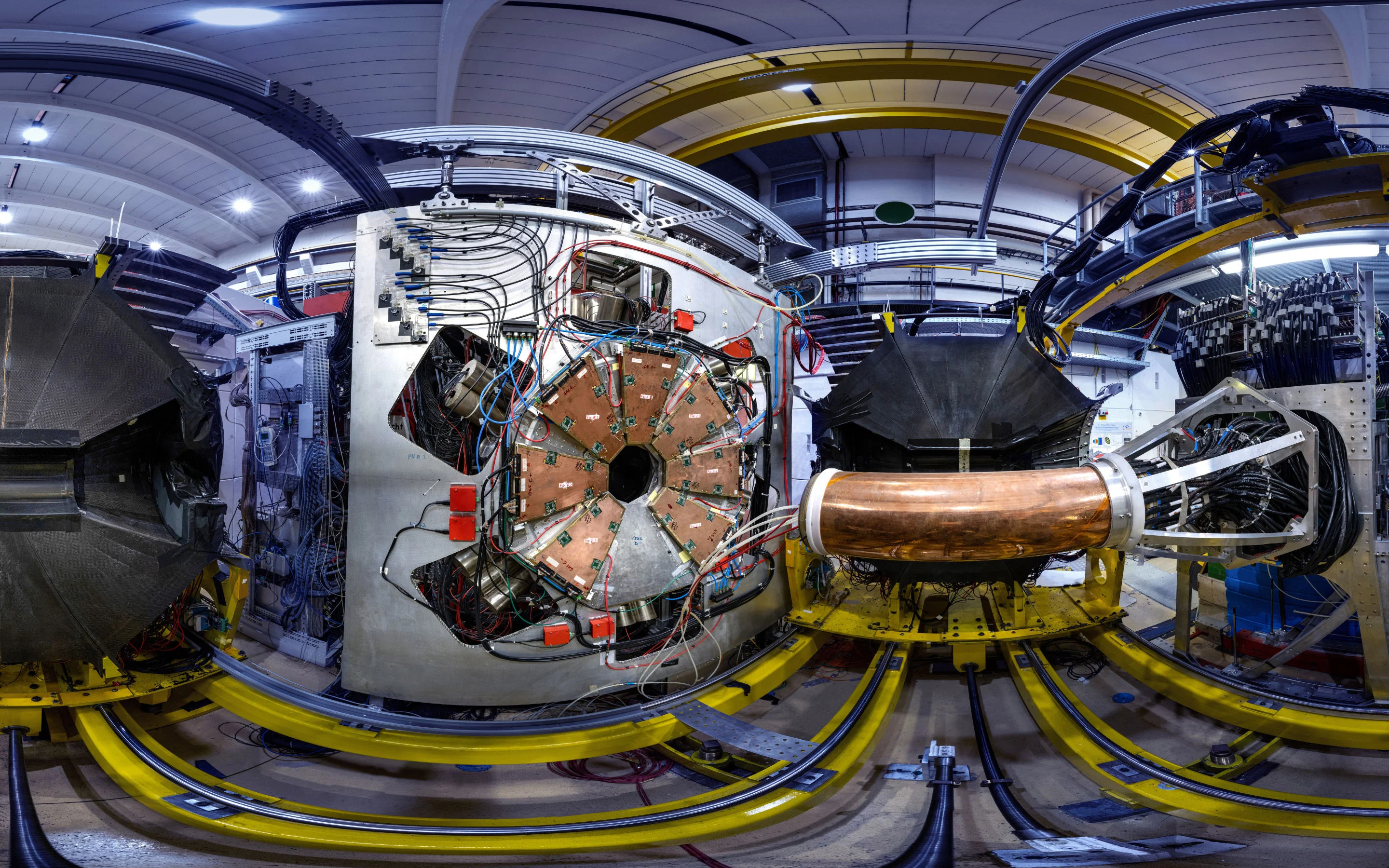

The physicians’ hunt for new phenomena on the smallest of all length scales requires instruments of a vastly different magnitude. In order to cover the whole energy spectrum for its investigations, the Cluster of Excellence is involved in several large-scale experiments all over the world. These include the Belle II experiment at the KEK research center for particle physics in Japan, while the members of Color meets Flavor are also contributing their expertise to the ATLAS, AMBER and LHCb experiments at CERN in Geneva.

However, the project partners—TU Dortmund, the University of Siegen and Forschungszentrum Jülich as well as the University of Bonn—are also providing some of the experiments themselves. “We have some robust infrastructure at our disposal at the University of Bonn,” Dingfelder says. This includes the ELSA particle accelerator, which is used for experiments involving relatively low energy levels. “We’ll be using ELSA to set up the new INSIGHT experiment, for example, which will allow us to study the strong interaction and the bonding states of quarks in even greater detail.” Some of the parts for the detector that INSIGHT will need are being built at the University of Bonn’s Research and Technology Center for Detector Physics (FTD). The FTD provides infrastructure and measurement laboratories at the highest international standard to develop detectors that meet the ever-growing demands of top-level researchers.

“My dream result would be to discover a new phenomenon in particle physics—but it’s also extremely exciting to run really precise measurements on processes that are already familiar to us,” says Dingfelder, summing up.

These clusters will continue to receive funding

Between “free” and “not free”

Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies (BCDSS)

Taken prisoner in East Africa, transported to Mauritius via illegal slave trade routes and forced into labor or military service: this is the story behind the 58 faces on the busts that ethnographer Eugène de Froberville collected in Mauritius during the 1840s.

In a research project, Klara Boyer-Rossol compared the original plaster busts against Eugène de Froberville’s manuscripts and thus identified virtually the whole collection and traced the names and life stories of the African ex-captives. She then made them accessible to the general public in a number of exhibitions, investigating the relationship between slavery, colonial dependencies and museums’ collection practices in the process. This is just one example of the research work done by the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies (BCDSS), which has been offering new perspectives on slavery and dependency research since 2019. Researchers from 43 different fields collaborate across discipline boundaries with 24 international partner institutions to conduct historical studies of deep-rooted social dependencies from different times and parts of the world while taking account of all shades on the spectrum between “free” and “not free.”

During the next funding period, its members will be investigating some of the causes and mechanisms that contrive to maintain strong asymmetric dependencies in both historical and contemporary contexts. Why do slavery, forced labor, domestic servitude and sexual exploitation persist despite continued efforts to end them? Through its research, the BCDSS is doing much to answer the question of how people can live together more equitably in the future. It aims to establish historically informed dependency studies as an interdisciplinary research field in its own right and thus encourage and empower researchers in the humanities and social sciences to integrate analyses of strong asymmetric dependencies systematically into their studies of social, economic and cultural phenomena.

How did European countries respond to the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and what measures actually helped cushion the blow? It was questions like this that ECONtribute: Markets & Public Policy—the economics Cluster of Excellence at the University of Bonn—addressed in its first funding period.

For instance, one of its members, Professor Christian Bayer, analyzed three policy instruments in collaboration with his co-authors: national energy subsidies, a coordinated subsidy at EU level and targeted money transfers to individual households. They found that, although national subsidies can bolster the domestic economy in the short term, they harm other European countries on the continent’s highly interconnected gas market. Targeted money transfers prove to be a fairer and more effective alternative. These payments, which are made to citizens based on their gas usage, lower the cost of living without distorting prices on the energy market any further without impacting negatively on other EU countries. On the contrary, these transfers even have the potential to increase prosperity in the country making them.

With research projects like this, ECONtribute is aiming to gain a better understanding of some of the urgent societal and technological challenges that we face. Researchers drawn from economics, business administration, psychology, ethics, social sciences, politics and law are devising innovative approaches to analyzing markets and policy. Their research focuses on the human element—people’s beliefs, expectations and sense of justice, in other words: all key factors for identifying sound recommendations for shaping markets and policy measures. During the upcoming funding period, they will be grappling with questions such as “Under what conditions will policy measures be accepted by society?”, “How can economies be made more resilient in times of crisis?” and “How can short-term measures be balanced with long-term political aims?”

The over 80 research groups in the ImmunoSensation Cluster of Excellence, which was set up in 2012, all have one thing in common: they see the immune system as a “sensory organ.” Drawn from the fields of immunology, neuroscience, system biology, bioinformatics, mathematics and clinical research, they have played a big part in identifying and characterizing key innate immune system sensors, decoded new immune activations mechanisms and elevated the concept of immune sensing to international prominence. For example, the team led by Professor Hiroki Kato from the Institute of Cardiovascular Immunology at the University Hospital Bonn has discovered an active substance that inhibits MTr1, an enzyme produced by the body, thus curbing the replication of influenza viruses.

This substance has been shown to be effective in lung tissue samples and mouse studies as well as in combination with approved flu remedies. This new approach secured Professor Kato $2.2 million in funding from Open Philanthropy. The project being funded is geared toward identifying other MTr1 inhibitors that work on flu and that could form part of clinical trials before too long.

This is just one of the many successful research projects on which the researchers will be building in the upcoming funding period, for which their cluster is being rechristened ImmunoSensation3. In scientific terms, their challenge for the next seven years will be to conduct systematic research into immune diversity. The structure, function and dynamics of the immune system are constantly changing in response to genetic factors, environmental influences, our lifestyle, our sex, our age and any previous medical conditions we might have had. These influences are reflected in our body at the molecular, cellular and systemic levels and are what makes every immune system unique, and “immune diversity” is the name given to the resulting natural heterogeneity. ImmunoSensation3 aims to develop a better understanding of the immune system’s variability in order to pave the way for tailored, precise diagnosis, prevention and treatment strategies.

Mathematics has the power to improve medical applications in some very tangible ways. For instance, physicians employ magnetic resonance imaging to shed light on pathological changes inside the human body. This frequently involves using contrast agents that are often not only expensive but also bad for the environment and, potentially, for our health too. However, a combination of numerical methods and machine learning has enabled Alexander Effland from the Hausdorff Center of Mathematics (HCM) to reduce the dose of contrast agent required significantly. Not only does his method not erode the quality of the imaging, it even makes for more informative diagnoses.

The success of the technique prompted Alexander Effland to form the start-up relios.vision together with colleagues from the University Hospital Bonn. The company, which has already won multiple awards, is a shining example of how mathematics research can produce direct innovations relevant to society. However, medical applications are just one area in which the HCM’s members are involved. Established back in 2006, the cluster—the first for mathematics anywhere in Germany—covers a wide range, from ambitious basic research through to industrial applications. And it has proven extremely successful at this, growing to become an internationally significant center for mathematical research and teaching and for academic dialogue.

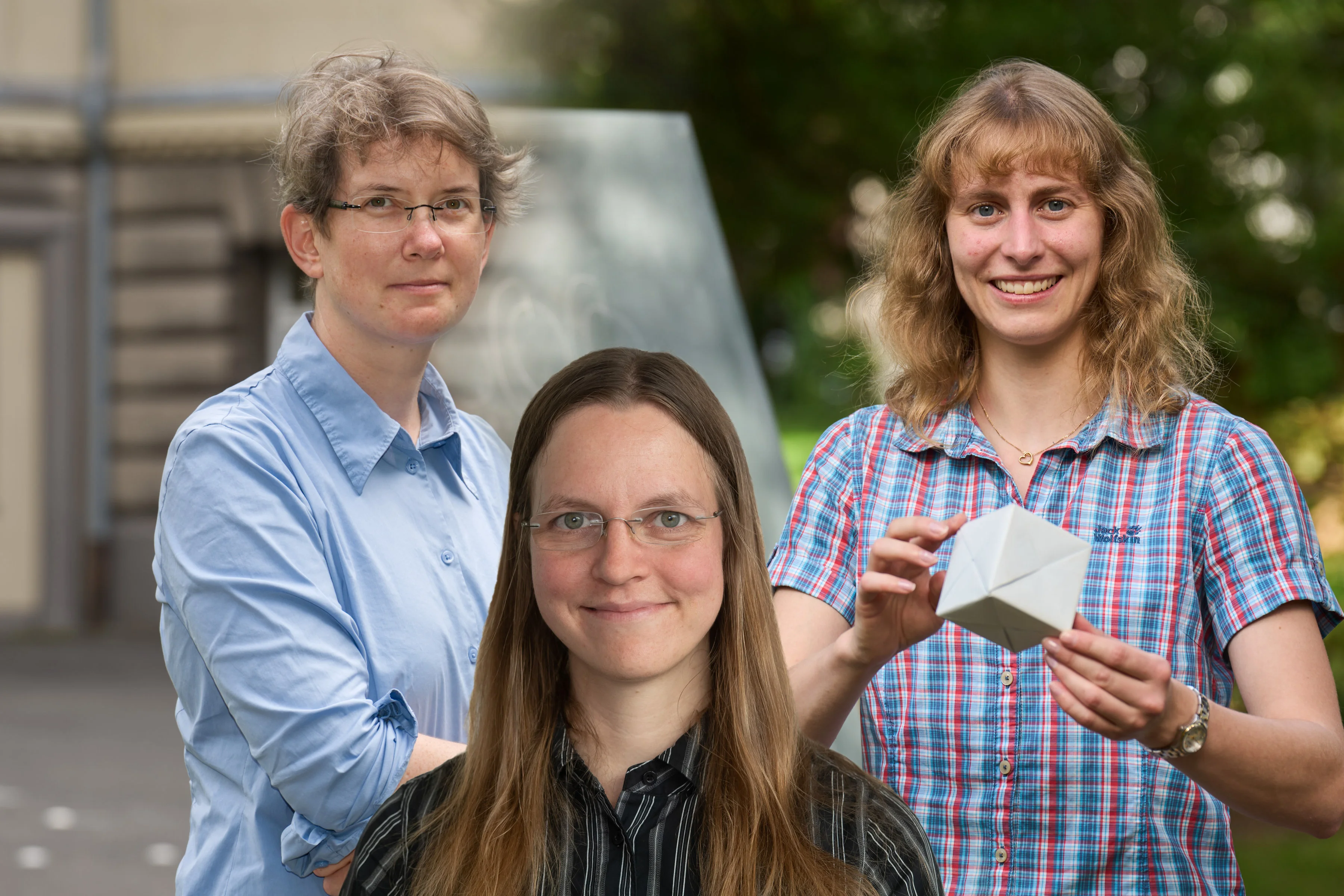

The HCM produces a host of world-renowned award winners every year. The HCM will be entering its fourth funding period with a whole squad of new reinforcements, including some world-class female mathematicians such as Jessica Fintzen, Angkana Rüland and Lisa Sauermann. Top of its new research agenda will be continued progress with the Langlands program plus, in applied mathematics, inverse problems and combinatorial optimization with industrial applications. A new interdisciplinary research unit has been set up to add new sections, such as harmonic analysis, to the library for the Lean proof assistant and, in the long term, to make the formalization of mathematics standard practice.

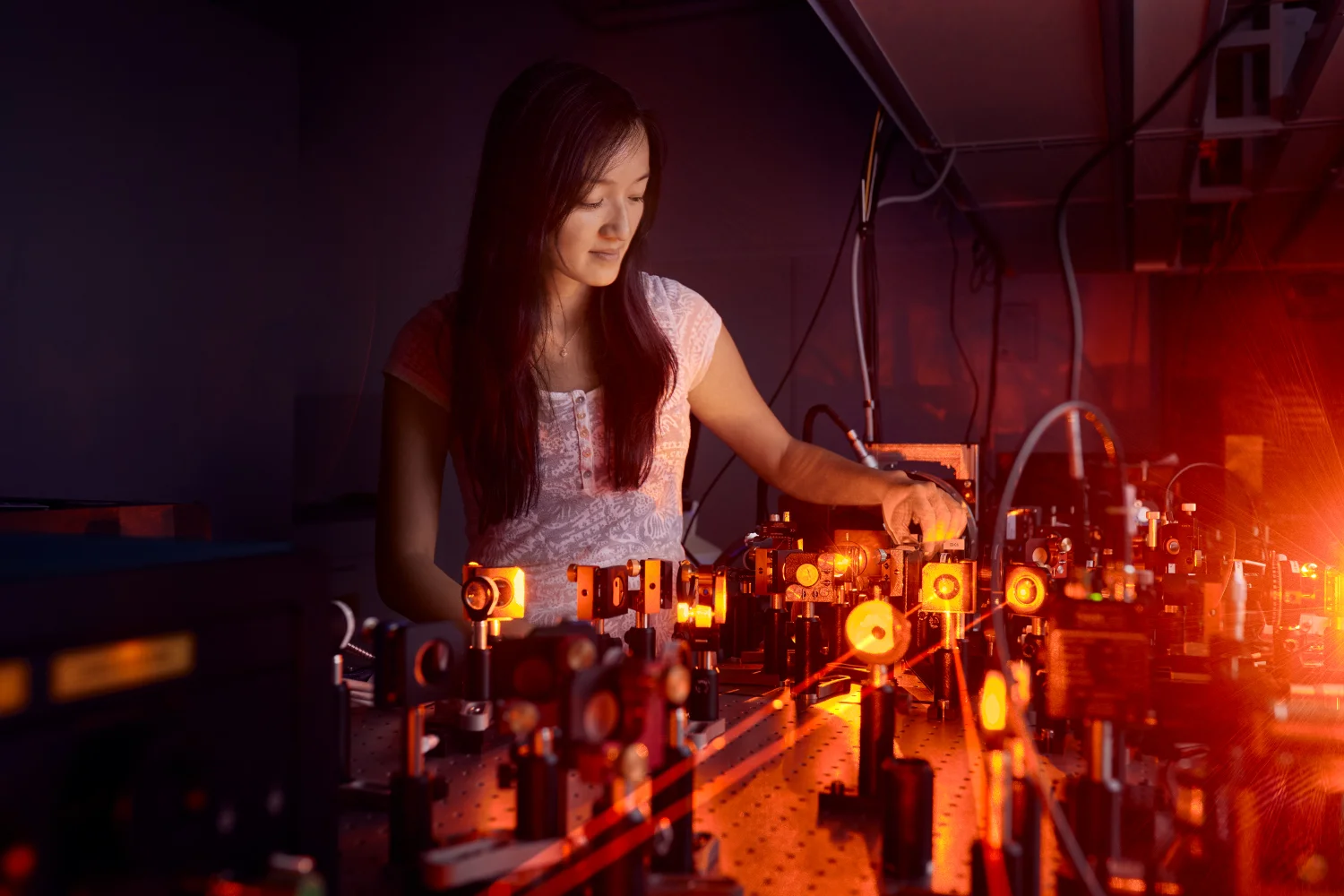

The ML4Q Cluster of Excellence studies the principles underlying innovative hardware and software for quantum computers. The researchers from the fields of solid state physics, quantum optics and quantum information theory investigate technologies that are still in their infancy but have the potential to transform quantum information science. Physicists at the University of Bonn have gained a reputation as a driving force in research into Bose-Einstein condensates (BECs) formed from photons. In particular, the close collaboration between the cluster’s experimental and theoretical wings—most notably in Bonn and Düsseldorf—has opened up new perspectives for future quantum networks.

Photon condensates are proving a highly promising avenue for answering fundamental questions of quantum matter. Led by Martin Weitz, the group at the University of Bonn has successfully demonstrated that photons can be placed into a collective quantum state through targeted manipulation inside an optical resonator. These findings led the cluster’s researchers to discover new quantum states of photons and run experiments to study them. One major leap forward came with controlling the dynamics of photon BECs in a “double-well” potential—a key step toward complex optical quantum structures. For the first time, it was possible to analyze phase transitions in systems of this kind and calculate the compressibility of a photon gas. As well as deepening our understanding of physics, this work is also furnishing useful insights for quantum information processing.

It is research like this that has seen the cluster establish itself as a breeding ground for a whole “quantum ecosystem” in the Rhineland. In the second funding period, which starts in January 2026, this breeding ground will produce a number of new structures that will bring research, training and social participation even closer together: a Quantum Career Center, a Software Hub, and a Center for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion.

PhenoRob has set itself the goal of revolutionizing crop production and making it more sustainable. Its researchers—from the fields of robotics, geodesy, computer science, plant phenotyping, soil science, crop science, ecology and agricultural economics—are collaborating on new approaches for making agricultural cultivation more sustainable with the help of cutting-edge technologies. This means shrinking its environmental footprint, preserving soil and arable land quality and demonstrating the best ways to introduce new technologies.

Meter by meter, the small four-wheeled robot traverses the field, locates the plants growing in it, classifies them and counts them. If it spots any weeds, it switches to tackling them—using chemicals, mechanical means or a laser beam as necessary. Rather than eliminating all weeds across the board, it is only interested in the harmful ones. Adopting this method means that, besides improving the microclimate and preventing soil erosion, the “BonnBot” is also promoting plant and insect biodiversity while also cutting farmers’ operating costs. Yet the robot is just one of the technologies that the PhenoRob Cluster of Excellence developed during its first funding period. Alongside undertaking basic research, the cluster also aims to translate its findings into practice. Its “BonnBot” from the first funding phase, for instance, has evolved into a start-up with the name of DynamoBot.

PhenoRob, whose Speakers are Professor Cyrill Stachniss and Professor Heiner Kuhlmann, will devote its second funding phase to consolidating and expanding on its interdisciplinary approach to research, focusing on developing new, sustainable cultivation systems that combine environmental, economic and social aspects. Key topics will include autonomous agricultural robots, AI-powered crop production, sensor-based phenotyping, analyzing cultivation systems and integrating them into society and policymaking in order to promote a holistic understanding of what future-proof agriculture looks like.

Excellent prospects: University of Bonn continues its success story

The University of Bonn will be home to eight Clusters of Excellence from January 2026 onward, more than any other university in Germany. Thanks to this tremendous achievement, the University of Excellence will once again be going into the nationwide Excellence contest as the most successful entrant. This also sets the stage for the second funding line: a decision on the future of the current universities of excellence will be made in March 2026. On one particular evening in May, the popping of champagne corks could be heard inside the Rectorate building on Dechenstraße. After all, there were no fewer than eight good reasons to celebrate: “This is a historic landmark achievement for our University,” said Rector Professor Michael Hoch. “That we’ve beaten our sensational result from the last round and now secured eight clusters is nothing short of outstanding.” There was a relaxed mood inside the atrium, where around two hundred researchers from the eight clusters as well as members of University bodies and staff had gathered. They were celebrating an unprecedented success that was scarcely believable: not only had the University been awarded more clusters than ever before, it had scooped as many as both Munich universities put together.

With a hand in six clusters, the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences is just as well represented as the University of Tübingen all on its own and ahead of the University of Cologne, which “only” secured five clusters. The University’s Department of Physics alone has three Clusters of Excellence, as many as the whole of RWTH Aachen University. The Rhineland is a leading center of science in Germany on the “Excellence map.”

This outstanding result consolidates the University of Bonn’s position as the leading research university in Germany and one of the universities with the strongest track records for research in Europe and the whole world. Says Rector Hoch: “Our Clusters of Excellence—of which there are now eight—are already world-renowned centers of cutting-edge research and prove our academic and scientific capabilities across the board. They also give us a massive amount of momentum for our future strategy as a University of Excellence with a global network.”

The decision on the Clusters of Excellence was announced in Bonn in May 2025 by the Excellence Commission, made up of international researchers and the ministers of science and research at federal and state level.The 10 existing Universities of Excellence submitted self-penned reports on the past seven-year funding period and their plans for the upcoming one in the summer of this year and are currently being “inspected.”In addition to the ten existing universities and networks of excellence, 15 other universities and networks are applying for a total of 15 possible funding places. The new applications will be reviewed in spring and summer 2026. The Excellence Commission will decide on new admissions to the circle of universities and networks of excellence at the beginning of October 2026.