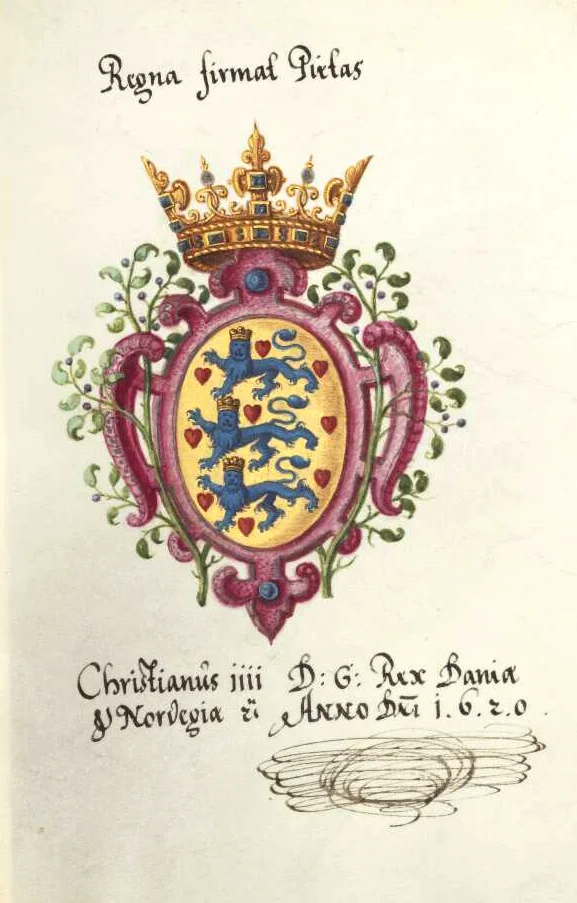

“Never change” and “Don’t forget me”—who could forget the sayings and wishes that we wrote in our friends’ books when we were little? A ritual that is nowadays largely the preserve of children or a town’s official guestbook was common practice among the traveling nobility a few centuries ago. Aphorisms, coats of arms and sketches were collected in Stammbücher, or “family albums,” and are now documented in the Repertorium Alborum Amicorum.

“Besides serving as mementos, these autograph books were also an expression of social ties and networks,” explains Jonas Bechtold. “People wanted to show off who they knew.” This trend would go on to encompass all groups in society, right down to kindergartners. “Friendship books like these still exist today, only mainly in digital form, such as in social networks,” Bechtold says.

The Stammbücher of the art collector and art dealer Philipp Hainhofer (1578–1647), a real political influencer of his day, are one particularly striking example. Books like these provide a venerable wealth of information for researchers studying complex networks of relationships or Alltagsgeschichte.

But Hainhofer’s Stammbücher are not the only sources included in the “Datendonner” project: platforms such as Old Maps Online let users superimpose historical maps on modern plans of towns and cities. For example, French maps dating from the 17th and 18th centuries show the bastion that formed part of Bonn’s fortifications as well as the Beuler Schanze, a raised defensive structure on the opposite bank of the Rhine. Where the Kennedybrücke links Bonn and Beuel today, the separation between the two places was still clearly evident back around 1850. By 1898, the piers of what would become the Rheinbrücke are already visible on the maps; Beuel has grown and is showing increasing signs of urban sprawl.

![Conventional pictorial elements were used here to create a very confident and radiant representation of the houses of Brandenburg and Württemberg. The entry was created with Barbara Sophia, Duchess of Württemberg, née Margravine of Brandenburg. The motto, abbreviated as MVSICA, can be interpreted as either: M[y] T[rust] R[esides] I[n] C[hristo] A[lone] or: M[ea] V[nica] S[pes] I[esus] C[ristus] A[men], meaning: My only hope is Jesus Christ. Amen. Translated with DeepL.com (free version)](https://www.uni-bonn.de/en/news/miniature-digital-treasure-troves-for-budding-historians/seiten-aus-mss_355-noviss-8f_eb01-schraegdoppels180-1_online.jpg/@@images/image)

Some 100 databases have already been released as part of the project, with many more in the pipeline. Each new “Datendonner” post presents a different historical database or digital edition in a compact, vivid and accessible format. Rather than archive materials in the traditional sense, these are all edited or publicly accessible sources: contracts, sketches or curiosities such as Leonardo da Vinci’s journal. “One of my favorite databases is ‘Neue unbekannte Lande,’ or ‘New, Unknown Lands,’ an edition of early explorers’ reports,” Bechtold reveals. “These sources come from people who were sailing the Atlantic around 1500. Even though much of the material is hard to decipher and no longer relevant today, how it depicts the perception of ‘foreignness’ and the discovery of a new world is unbelievably exciting—both for historians and for historical linguists.”

“Datendonner” is facilitating practical use of all these sources. The posts show students how to work with sources and how tackling them early on can improve the quality of academic work. “We often find that students stick rigidly to their secondary literature when writing term papers,” Bechtold points out. “They find it hard to make the leap to the original source.” This is not because of a lack of enthusiasm, he says, but rather to a lack of guidance or confidence. Initiatives that students are introduced to at an early stage, such as “Datendonner,” are helping to lower this particular barrier, making them more confident and giving their work greater depth. “Rather than running the risk of simply copying someone else’s essay, they work more independently.”

It all began a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic, originally as an idea to present some special collections from the former State Library of History in electronic form. Then came lockdown, which removed all the alternatives to digital formats at a stroke. The concept was adapted with the help of a student assistant, turning a makeshift solution into a format that would remain viable over the long term. “We were able to demonstrate that you can also do some good work with sources from the comfort of your own home,” Bechtold explains. “And we simply stuck at it.”

What began life as proseminar material has now unleashed a dynamic of its very own. Besides the presentations on Instagram and the seminar sessions, partnerships with Gymnasien in Bonn are also planned. “We want to show schoolchildren at an early stage that a source is more than just three lines in their textbook,” says Bechtold. For example, they could explore early-modern travel journals online before going on to view the originals in Bonn in person.

The project is financed from the institute’s own funds, as are many of the databases that have been put online over the last 30 to 40 years and are still accessible today, even if some of them now seem somewhat fusty. Not all the databases are as large as those of the Bodleian Library or commercial services such as EEBO (Early English Books Online), which covers all English printed works up to 1800. “Many digital collections are the result of research projects done by individuals who then make their holdings accessible to others,” Bechtold explains.

The weekly Datendonner updates will continue for some time yet to ensure that these digital treasure troves remain visible. After all, there are still several hundred of these collections waiting to be unearthed.

![Mit konventionellen Bildbestandteilen wurde hier eine sehr selbstbewusst strahlende Darstellung der Häuser Brandenburg und Württemberg geschaffen. Der Eintrag entstand mit Barbara Sophia Herzogin zu Württemberg, geboren Markgräfin zur Brandenburg. ie mit MVSICA abgekürzte Devise lautet aufgelöst entweder: M[ein] V[ertrauen] S[teht] I[n] C[hristo] A[llein] oder: M[ea] V[nica] S[pes] I[esus] C[ristus] A[men], also: Meine einzige Hoffnung ist Jesus Christus. Amen. Mit konventionellen Bildbestandteilen wurde hier eine sehr selbstbewusst strahlende Darstellung der Häuser Brandenburg und Württemberg geschaffen. Der Eintrag entstand mit Barbara Sophia Herzogin zu Württemberg, geboren Markgräfin zur Brandenburg. ie mit MVSICA abgekürzte Devise lautet aufgelöst entweder: M[ein] V[ertrauen] S[teht] I[n] C[hristo] A[llein] oder: M[ea] V[nica] S[pes] I[esus] C[ristus] A[men], also: Meine einzige Hoffnung ist Jesus Christus. Amen.](https://www.uni-bonn.de/en/news/miniature-digital-treasure-troves-for-budding-historians/seiten-aus-mss_355-noviss-8f_eb01-schraegdoppels180-1_online.jpg/@@images/image/leadimagesize)