Stretching across thousands of kilometres from Central Asia to eastern China, the Eastern Eurasian Steppe has long been a hub of migration, innovation, and cultural exchange. This latest interdisciplinary research sheds new light on prehistoric population dynamics in central Mongolia. By analysing human genomes alongside burial practices, the team uncovered evidence that two genetically and culturally distinct groups of Bronze Age herders lived side by side for centuries—until the emergence and spread of the so-called Slab Grave culture in the Early Iron Age displaced them.

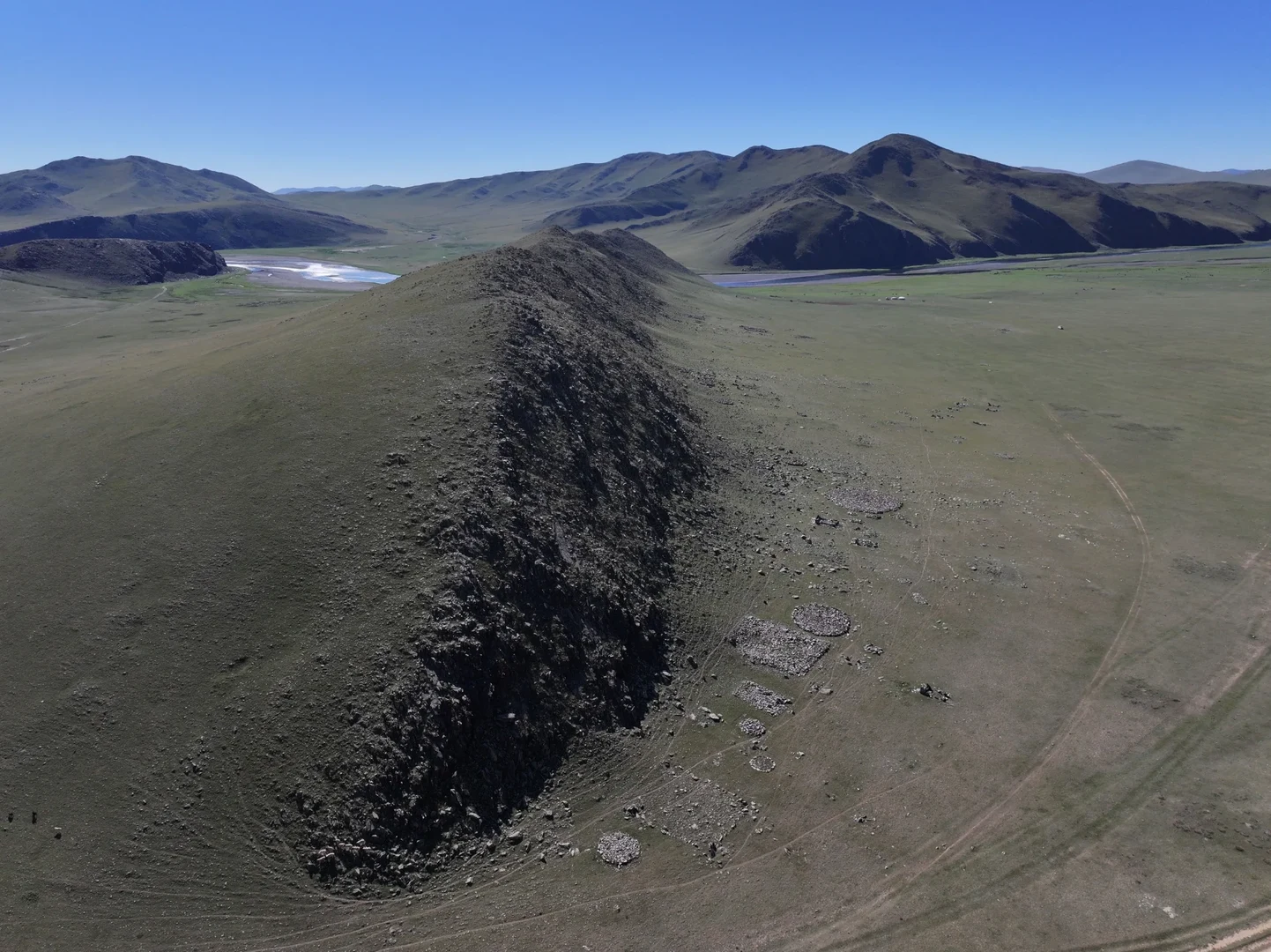

The study focuses on two nomadic groups that lived in Mongolia during the second and first millennia BCE. One group was centred in the south and southeast of the country, while the other occupied areas stretching from western to central Mongolia. These two populations came into contact in the Orkhon Valley of central Mongolia, where they even shared the same ritual landscape—burying their dead on the slopes of the same mountain.

Archaeological investigations revealed marked differences in the way each group laid their dead to rest. Individuals from the western group were buried facing northwest, while those from the eastern group were oriented towards the southeast. The burial structures themselves also reflect cultural divergence: while the western group built stone mounds typical of the so-called Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex (DSKC), the eastern group favoured smaller, figure-shaped stone graves.

The study’s interdisciplinary approach deepens our understanding of this phenomenon. “Our analysis of ancient human DNA shows that these two groups remained genetically distinct for around 500 years, despite living in close proximity,” explains Dr Ursula Brosseder, Head of the Prehistory Department at LEIZA and co-first author of the study. She adds, “Globally, we have very few examples from prehistory where we can identify such patterns or the underlying social rules that shaped marriage practices.”

With the onset of the Early Iron Age (around 1000 to 300 BCE), a new burial tradition gained prominence. Graves now featured enclosures made from stone slabs. This Slab Grave culture evolved from the eastern tradition of figure-shaped burials, rapidly spread westwards, and ultimately supplanted the burial customs of the western group. “Our new data show that this shift was not only cultural but also genetic,” says Jan Bemmann, professor of prehistoric and early historical archaeology and member of the transdisciplinary research areas “Individuals & Societies” and “Present Pasts” at the University of Bonn. “The genetic profiles of individuals buried in Slab Graves show little connection to the previously dominant western groups. This suggests that a large wave of newcomers from the east entered the region, replacing the western population almost entirely. Even centuries later, during the Xiongnu Empire (200 BCE to 100 CE)—which was known for integrating diverse groups—there is no genomic trace of the earlier western population.”

The study also confirms that the western population’s genetic roots can be partially traced back to the early Afanasievo and Khemtseg cultures—communities that introduced mobile pastoralism to Central Asia more than 2,000 years ago. This reveals a genetic legacy spanning several millennia.

“Our study makes an important contribution to our understanding of how genetic identity and cultural practice interacted in one of the world’s oldest regions of animal husbandry,” says Brosseder. “It demonstrates that cultural coexistence does not necessarily lead to genetic mixing—a phenomenon with profound implications for how we interpret early human societies and their dynamics.”