“Children and young people will encounter sorting processes of some kind at various stages of their school journey,” says Dr. Hanno Kruse, who recently took charge of an Emmy Noether research group in the Department for Political Sciences and Sociology at the University of Bonn. This includes when they leave their Grundschule and move on to a secondary school, which can take one of several forms. “There’s a lot of societal importance attached to sorting processes in schools,” the sociologist explains. “Besides setting the course for an individual’s school career, they also determine how marked inequalities will be in a society, such as ethnic background, gender or social class.” After all, not everyone undergoes school sorting processes in the same way.

Some sorting processes are designed to allocate children and young people to classes within the same school rather than distribute them between different ones. Says Kruse: “Senior leadership teams and teachers put children and young people into specific classes and on specific courses, which has a significant impact on the social relationships between the individual schoolchildren.” This is because what class a child or young person is put in will have a decisive impact on their daily life at school, influencing who they spend time with day to day and form friendships, identities and behavior patterns together. Whether or not these behavior patterns develop along ethnic, gender-based or class-specific group boundaries thus depends largely on sorting decisions made within the children’s school.

Effects on relationships, identities and behaviors

The SPINS Emmy Noether research group is focusing on the sorting decisions that senior leadership teams (SLTs) and teachers make regarding the composition of their classes. “We’re exploring the question of how these decisions affect schoolchildren’s social relationships, identities and behaviors,” Kruse explains. SLTs and teachers have a big decision to make in the run-up to every new school year, namely what classes to put their newcomers in. Many schools ensure gender balance among their classes, while a less common option is to sort children based on what Grundschule they are coming from. Sometimes, the schoolchildren’s own preferences for new classmates are taken into account too, while sorting processes can also be guided by artistic ability or language lessons.

SLTs and teachers wield significant influence

“Even though the sorting decisions they make seem small in scope, SLTs and teachers exert a major influence on the peer dynamics within their classes,” Kruse says. His project is studying how this potential can be leveraged to strengthen cohesion and avoid social divides within individual classes. As well as conducting a series of secondary-data analyses, the research team is also planning a nationwide field experiment. This will be accompanied by a multi-year survey targeting teachers and schoolchildren and is set to incorporate data from the local education authorities. Plans are also under way for partnerships with the University of Cologne and Princeton University in the US.

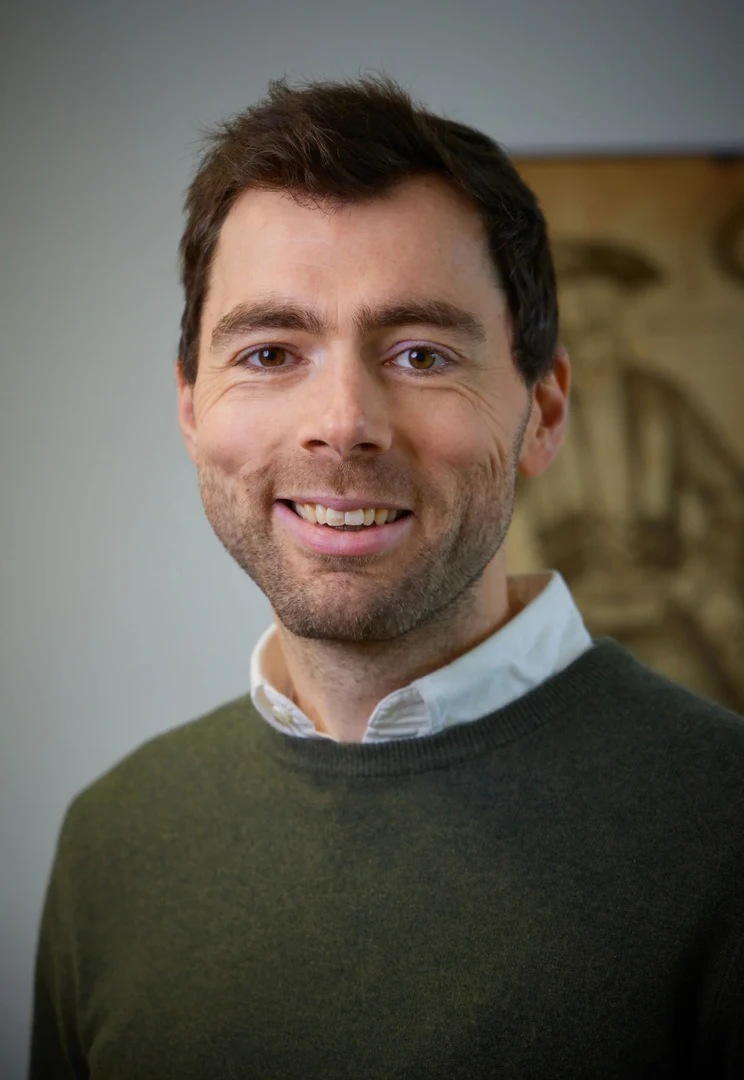

About Hanno Kruse

Born in 1985, Hanno Kruse studied sociology and economics at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and the University of Mannheim. After obtaining his doctorate, he moved on to do research work at the University of Cologne. He was an assistant professor at the University of Amsterdam prior to taking up his position as head of the Emmy Noether research group at the University of Bonn. Kruse is a member of the University’s Individuals, Institutions and Societies Transdisciplinary Research Area.

The DFG’s Emmy Noether Program gives high-caliber early-career researchers the opportunity to qualify as a full university professor within six years by leading a research group under their own responsibility.

Website: https://hannokruse.com/spins/